Vol 131 of NAEE’s journal, Environmental Education, is a special edition devoted to the circular economy. It is currently available only to our members but it will appear on our open web pages later in the year. This is Ken Webster’s Guest Editorial:

It’s a very confusing world, but perhaps it always was. Err…not like this. There is a war in Europe. The latest IPCC report says we are about out of time on climate. There is a pandemic of course and social media is a bewildering mix of information, misinformation, falsehoods and noise – anti vaxx anyone? In a barely understandable real world – but one where young people also grasp that there is a growing gap between what their prospects for advancement are compared to those of their parents or grandparents – it is hard going making the case for context-seeking educational work of the kind epitomised by environmental education. But, in another sense, what else could be more important if it means exploring changing perspectives? What we have is not working very well after all. I often quote Einstein here: “the theory determines what we observe”. Engaging and testing different frameworks for thinking is surely core to educational aspirations: or it should be in these most volatile and unstable times. And what better for learners than learning how to think abstractly as well as practically. It’s a pity, some might then observe, that there is so much overlap in the arena most of interest here. Once upon a time there was environmental education, then education for sustainable development (ESD), and eventually the big list (SDGs) and then a ‘circular economy’.

Circular economy as a term has ramped up over the decade since it was reframed and re-presented (in the West at least) around 2011 and 2012 as “an economic opportunity driven by innovation” (Stahel). Like almost every general conceptualisation – including such well debated ideas as ‘democracy’ or ‘justice’ – there are many so called definitions. Not a problem, really, as it’s a perspective not a machine. However, there is an easy to grasp, intuitive sense to ‘circular economy’ as being the opposite to a ‘take-make-use-and-dispose’ linear economy, characteristic of the first industrial revolution, especially as it became wildly more productive in the mid/late 20th century.

A circular economy is most often about rethinking the answer to the economic question ‘How do we produce?’ How about the notion of maintaining or building capitals (natural, social etc), designing and creating products, components and materials as if they were ‘nutrients’ for the system as a whole? How about shifting from goods to services and to renewable energies? Oh, and there might be some recycling in there too. Circular economy is not a new idea but a synthetic and umbrella concept – and the result of conscious synthesis. In its current form, it is a synthetic framed for policy and business impact. Here is one part of that story and it goes to the heart of what I was seeing in schools and elsewhere in the run up to the 21st century. It helps think through the relationship between EE and CE and it has, I argue, an excellent outcome for environmental educators.

I was a former economics educator who got involved with environmental education (largely through WWF and Field Studies Council contracts) and later education for sustainability in its different forms as an educational writer and in-service educator. I was increasingly frustrated by the lack of systems thinking (understanding that most real world systems are feedback rich interdependent non-linear systems, if you want the jargon). The pedagogical approach which matched dynamic systems – more participatory or active learning – was a minority interest for busy and constrained teaching colleagues in siloed positions. Sustainability in schools felt like waste management fixes, recycling (of course); do with less, ‘walk, don’t take the car’, with some solid science around climate change, biodiversity and poverty in developing countries. Good work in many a classroom and institution kept spirits up. Curiously, almost pre-industrial but romantic notions of a kind of frugal localism popped up too. In short, there was too little contemporary economic and business understanding and a recognition of the potential of radical product re-design. It was frustrating, especially since I had come across the work of Bill McDonough and Michael Braungart in cradle to cradle, Janine Benyus in biomimicry, Walter Stahel, and Gunter Pauli. I was enthused to write a short book with Craig Johnson called Sense and Sustainability which made the case for a systems perspective, teaching and learning to match and a living systems inspired look at product design use and onward. I was then sure that I would have no new contracts for educational work at all and was prepping for a return to teaching economics in 2008.

Someone interesting read my book, however. As a result I advised positioning the work of the embryonic Ellen MacArthur Foundation, at least in education to begin with, as focussed on systemic change (not the individual) – particularly the ‘rules of the game’ or enabling conditions around, say, taxes and regulation; on applying the lessons of cradle to cradle design and on creating a positive cycle (natural and social capital building) as opposed to a ‘do less harm/mind how you go’ attitude. This was exactly the kind of positive problem solving approach that Ellen MacArthur herself practised in her own specialism of yacht racing. In the Foundation context, taking care with the framing of the ideas, the use of language and playing solidly to business and policy interests, especially at EU level, circular economy became an heuristic for change which would (or could) support the delivery of the SDGs.

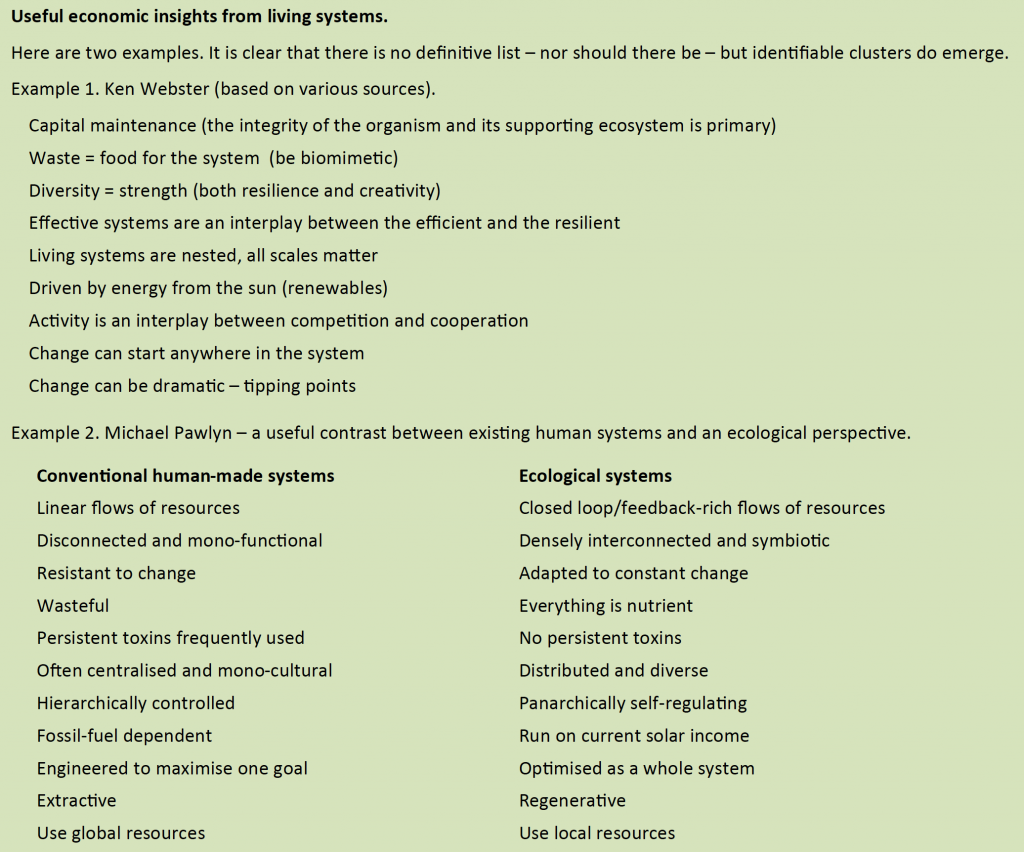

At the heart of this synthetic, deliberately framed heuristic called the circular economy remains the fact that the key writers alluded to above, and many since, have overwhelmingly used ‘insights from living systems’ as a guide. Living systems are a subset of a class of complex adaptive systems. In short, the very core of a perspective which potentially integrates business, economy and environment is one which many environmental educators not only understand but hold dear. Did they but activate it within the economic sphere/contexts they would see nothing but opportunity to ensure that environmental education is essential to creating the mindset which will enable a ‘regenerative circular economy for all’ (also the title of my new book, again with Craig Johnson).

I contend that shifting to a circular economy within planetary boundaries needs a different sense of economic processes and purpose. But also that systems perspective. It’s no easy task, not least because so often environment and economy seem competing spheres but surely it is time to reimagine their shared base and enthuse around ideas which seem to be emerging more strongly, even from this most troubled of times.

This is perfect for EE – systems thinking using insights from living systems to create a shared perspective to circular economy challenges and opportunities. Step to centre stage.

………………………………………….

Reference:

1. Stahel tinyurl.com/4x5xx6vk

Notes